The Westminster Commission on Forensic Science

Forensic Science in England and Wales: The Westminster Commission on Forensic Science Pulling Out of the Graveyard Spiral

TL, DR

A UK parliamentary group's report warns that England and Wales' forensic science system is in a "graveyard spiral" due to a broken private market, police underfunding leading to corner-cutting, damaging over-reliance on police in-house labs, and loss of expertise. Key recommendations include an urgent national audit and halting police lab expansion to stabilize services; creating a fully independent National Forensic Science Institute (NFSI) to set strategy, protect niche disciplines, and fund research; long-term removal of ALL forensic services (including crime scenes and digital forensics) from police control for impartiality; reforming legal aid to ensure fair access to defence experts; and addressing systemic issues like lost evidence and inadequate defence funding that contribute to miscarriages of justice. The report argues comprehensive reform is critical to restore independence, capability, and public trust in the criminal justice system.

Introduction

Taking a moment away from the fibres deep dive to talk about this report from the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) from their three-year inquiry into all things forensic science in England and Wales.

All-Party Parliamentary Groups (APPGs) are informal cross-party groups that have no official status within Parliament. They are run by and for Members of the Commons and Lords, though many choose to involve individuals and organisations from outside Parliament in their administration and activities.

So this is not a formal inquiry by government, nor does it have the status of a parliamentary inquiry by a parliamentary committee. It is “soft power”, seeking to influence policy through consensus. On that basis it seeks evidence from individuals and organisations that can inform them on selected topics.

This particular APPG is the All Party Parliamentary Group on Miscarriages of Justice. It was formed in November 2017 to examine the structural problems within the criminal justice system which result in miscarriages of justice, and to provide a forum to improve access to justice for those who have been wrongly convicted. This report is the second report it has produced, the first report they produced was on the work of the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC), entitled “In the Interests of Justice”.

The report on forensic science is well worth a read. As I have documented relentlessly on this substack, England and Wales, for many reasons, is a global outlier when it comes to the provision of forensic science. Whether we are the pioneers of a new way of doing forensic science efficiently and effectively or have completely lost the plot and ended up turning the clock backwards is a matter of opinion, this report seeks to clarify precisely where we are and suggest a means to move forward. This post is all about looking at some of what their recommendations are and what the implications of accepting them could mean.

The text in block quotes or pull quotes are taken directly from the report.

#1 - #2 “Stop the Rot”

While the crisis in forensic services provision might be largely explained by a combination of funding pressures, increased costs, and regulatory burdens, the current graveyard spiral has been accelerated by the continued paring back of demand from police, growth of in-house provision, and prioritisation of ‘rapid/cheap’ testing in sustained efforts to meet budgetary demands. The fragility and unprofitability of the forensic marketplace has led to reduced investment, with the monopolisation of full-service forensic science provision and extreme precarity among smaller providers. Both capacity and capabilities have narrowed resulting in impoverished forensic strategies and the endangerment of ‘niche’ disciplines.

Recommendation 1 - There should be a full national audit of forensic services, to assess what support can be urgently put in place, to shore up current provision and prevent further deterioration in capacity and capabilities whilst substantial reforms are commenced.

Recommendation 2 - Whilst reforms are being implemented, further expansion of police in-house provision should cease, and all police provision should operate in full.

Full national audit, that’s great, but who does this? It does need to be independent, so how about the National Audit Office (NAO)? Well the NAO has done audits like this before, last time in 2014 it audited The Home Office’s oversight of forensic services. This request however is far more complex, if it is the NAO who should do something like this, they are going to need a lot of help from forensic scientists embedded within it for the project.

Ok so the audit happens and identifies support, that is likely to require an injection of funds, if so how much? Will it mean reversal of the brain drain, recruitment and training? The appointment of an interim body to manage the emergency funding independent of the police that could perhaps morph into something permanent later? This looks quite challenging.

Getting the police to stop expanding in-house provision appears quite a tricky thing to do; policing is a devolved matter to either regional Mayors or Police Crime Commissioners so they would have to agree. Perhaps one way around that would be for the Forensic Regulator to simply instruct UKAS to halt all current and new accreditation applications by police in-house laboratories.

#3 “Improve Crime Scene Attendance”

Forensic science starts with timely, effective, scene attendance by expert examiners. Cutting corners at the outset leads to increased costs, lowered detection rates, slower investigations and weaker prosecution cases. This impacts negatively on public trust and confidence and increases the risk of miscarriages of justice. There should be an assessment made of the unmet demand and how this demand could be met.

Recommendation 3 - The effective and efficient attendance and examination of crime scenes must be scrutinised urgently and any inhibiting factors e.g. overly prescriptive approaches to accreditation, dealt with. Individual force policies on scene attendance should be set in line with nationally agreed best practice and monitored. All scenes should be examined to a proportionate extent, with meticulous and generous sampling, with all evidence properly archived, to facilitate future use.

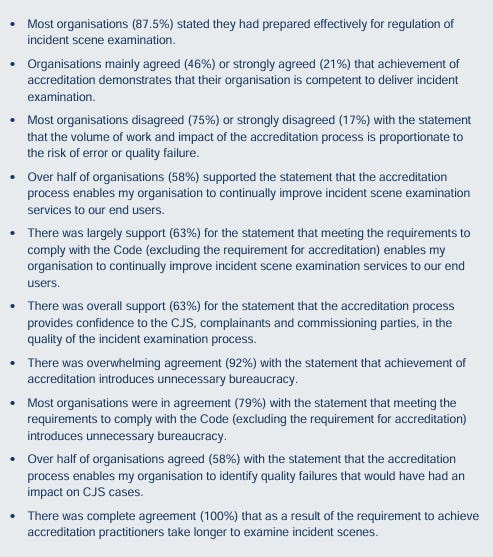

“Unmet demand” = not enough crime scenes being attended. A significant reason for that is how police forces have addressed meeting the ISO standards, largely by requiring those who attend scenes to take the burden of the paperwork associated with the activity. More time behind the desk means less crime scenes attended. Obviously, the knock on effects of this downstream to forensic science labs mean a reduction of volume of submissions. The Forensic Regulator has already started looking at this and the results of a consultation survey revealed:

So it would appear that there is general consensus that accreditation to ISO has had a detrimental operational effect on crime scene attendance. The FSR’s response has been to tweak the codes, which is the limit of the assistance the FSR can give in this regard, but it is an important tweak to identify that volume crime scenes perhaps do not need all the bells and whistles associated with homicide scenes when it comes to the paperwork needed to do the job.

Police forces do not have the best of track records of being able to agree on national approaches to do anything, so I am less optimistic that a national standard for crime scenes will be possible whilst crime scenes remain the domain of police forces. The review into the Forensic Capability Network commissioned by the National Police Chief Council laid that bare and the Home Secretary is on record as saying:

Take forensics, where the adoption of cutting-edge forensic science across the board has been held back by uncoordinated funding and fragmented governance, resulting in duplication of effort and an inability to implement strategic plans.

A major weakness throughout England and Wales is the storage of exhibits by police forces and it is important that it is recognised as an activity in its own right, this recommendation begins the acknowledgement of that.

#4-7 “Lines in the sand”

Police triaging of submissions impacts upon the potential of forensic investigations, as well as giving rise to concerns about independence and bias. The lack of collaboration between experienced police and scientists limits assistance with both forensic strategy and the interpretation of results. There is a lack of institutional support for investigators, particularly in respect of decision making and forensic strategies.

Recommendation 4 – His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) should scrutinise police forensic investigative strategy setting (including the use of tools such as CAI to ensure best forensic focus in triaging) and in-house provision of forensic services should be incorporated within PEEL inspections of investigative performance. This should include CSI provision, forensic submissions units, and forensic strategy within both volume and serious crime until longer term arrangements have been made for this activity to be transferred to independent organisations.

Recommendation 5 - Scientific support for police investigations must be strengthened. The National Police Chief’s Council (NPCC) and College of Policing, supported by Forensic Science Providers (FSPs), should immediately address the national shortage of trained detectives with experience in forensic investigations. There should be national prioritisation of both training and greater support for all investigators, particularly Senior Investigating Officers. Scientific support officers should be in place within all Criminal Investigation Departments.

Recommendation 6 - Both FSPs and police should work to create a trusted and transparent relationship, while maintaining their operational independence and respecting professional boundaries. This must include assisting with forensic strategy setting, deciding casework requirements. Police should work closely with FSPs to understand demand forecasting and how to best manage peaks and troughs in workload, rationalising any contractual penalties.

Recommendation 7 - The HMICFRS recommendation to bring digital forensic services under the wider forensic science structure should be acted upon. Thus, in the long term, digital forensics should be removed from direct police provision and be undertaken by independent specialist organisations working closely with investigative teams to ensure the rapid production of valuable, reliable information that supports active investigations from an impartial stance.

This is all about the battle over who gets into the exhibit bag first, what evidence is recovered when someone cuts into it and what happens when plan A (DNA and fingerprints) fails. The recommendations re-introduce the concept that scientists must have a say, where the recommendations are unclear is defining who really is in charge, what if the scientists disagree with police or vice-versa? If the police remain in control of the budget it will always be them, but if proper discussions between scientists and police regarding forensic strategy are held in every case they form part of disclosure. That alone will empower scientists because police may be reluctant to have to explain in court why they failed to take scientists advice. Right now this is just not happening the way it should with police not even entertaining being questioned by scientists:

The commoditisation of forensic science has super-charged such fragmentation, with exhibits split between forces and external providers. However, we were told by scientists that this can often prove a false economy, and investigations are delayed while work is repeated, or the scientists must spend their time interpreting requests from the police. Cellmark’s Managing Director explained that: “It’s a concern particularly in sexual offence investigations where if we [don’t receive] all the information up front, we ask questions quite rightly, and we’ve had complaints back asking why we are asking so many questions.”

Scientists repeated that they need to know much more about the totality of items seized and ideally be involved in decisions on what testing to undertake. They claimed that this rarely happens because detectives are too busy and such meetings are not ‘costed in’. We were also told of instances where prosecution experts have been surprised in court by evidence that defence experts had access to, but of which they were unaware, this evidence then required them to hastily re-evaluate their conclusions on the spot.

This works both ways of course as shown in the case of the murder of Georgina Edmonds.

#8-9 “The market”

At its inception, commercialisation was a success. Poorly conceived contracting arrangements, combined with years of austerity, resulted eventually in financial instability, downsizing and loss of scientists and companies. A situation which has worsened until we find ourselves today with a broken market. There is currently no incentive for new entrants into the market and little incentive for further investment. To address this, more realistic pricing and a better contracting model should provide for guaranteed returns which will encourage long term growth and investment. There are commercial providers committed to the sector, but they can only sustain this commitment if there is a future in the market. High quality scientists will only be retained through training, career progression opportunities and competitive salaries. These scientists must work in modern, well-equipped facilities, which support research and development. Any green shoots to be found across the sector, need support and reassurance of brighter days ahead.

Recommendation 8 - After stabilising what forensic provision remains, there must be a plan for re-creating a market and making it attractive for investment. To encourage new entrants and investment into the market, sustainable contracting and realistic costing must be introduced urgently. Pricing should reflect the true cost of delivering high quality forensic services, including the full range of activities required for casework and testing.

Recommendation 9 - The Association of Forensic Science Providers (AFSP) should become a trade association, and work with the police, Home Office and others, to re-calibrate contractual arrangements. The Forensic Science Regulator’s powers should be extended to include regulating the market.

No recommendations to return 100% provision of forensic services to the public sector. That may disappoint quite a large constituency inside forensic science and policing. Policing in general has always been hostile to the idea of profit making from forensic science, and that feeling has a large constituency amongst the general public too who generally dislike the idea of private companies profiteering from public services:

The Managing Director of Cellmark: “It doesn’t help that as a private organisation, somehow there is a concern [amongst police] that ‘they’re just trying to make money’, which is so ridiculously far from the truth”.

So why has the APPG fallen short of making a recommendation to nationalise the whole thing and start again? Well if you stop your car, roll down your window and ask an Irish person for directions you may get the response “if I was going there, I wouldn’t start from here”.

I believe that the APPG has looked at the private market and still see enough value within it that, under a specific set of circumstances, the market approach is still viable. It is undeniable that the private market has succeeded in delivering fast, low cost, high quality, volume DNA and drugs analysis. The weakness in the private market delivery system has been the supression in demand for absolutely everything else and arguably the root cause of that is the structural flaws in doing “the difficult stuff” that have never been properly addressed since the Forensic Science Service first started charging police forces so many moons ago.

The APPG do not hold back in its criticisms of the naivety of the FSS from the early days:

2.10 Between the forensic providers, there were highly competitive pricing wars to win essential contracts, and this often led to unrealistic costings, most clearly from the FSS who arguably lacked sufficient business acumen and were always under pressure to maintain their position as primary provider. A test could be significantly more costly than the police were being charged in some instances but would be ‘subsidised’ by other tests sold in large numbers. DNA testing for example, was often used to ‘balance the books.

As for the police, my observation as the owner of an SME in the market, being forced to be a subcontractor to a “big provider” was that what the police wanted from a market was not what the politicians imagined it to be. Far from being a playground consisting of a diverse ecosystem of small innovative companies and bigger providers, the police just wanted a cheap FSS that did everything and where they didn’t have to deal with the madness and chaos of multiple suppliers with differing points of view. We now have a single private FSS, but it’s a pale reflection of it in terms of resources and capacity. As the APPG say:

In reality, the UK has a monopoly situation with only one full-service provider - Eurofins Forensic Services - delivering over 85% of external forensic science provision.

So how on earth do we change the market from police’s apocalyptic vision of what they want it to be, to the politicians nirvana of a diverse ecosystem of suppliers? Money yes, ok. Higher prices. Ok. More suppliers, hmmmmmm.

Huge challenges with that.

You’d have to rip up the madness that is the current forensic procurement systems and lower the bar for accreditation to facilitate new entrants to the market. Allow new entrants to do casework whilst going through the hoops to get accreditation, processes would need to be put in place to mitigate the risks associated with that. Not impossible. Far from it. Accreditation is a badge, it does not prevent quality failures, there is plenty of evidence of that. After all, this is precisely how the police started their in-house laboratories so why should it be any different for private companies as new entrants? The precedent has been set.

Relax the need for a full service provision. It would be impossible for new entrants to enter the market and provide the full provision Eurofins can from day one. Let’s not forget Eurofins entered the market as a SME providing a limited service, they only became a full service supplier by buying LGC Forensics. Many SMEs would target only specific areas that currently now contractually require a “big provider that does everything” for reasons that no longer seem justifiable in the current market dynamic.

Eurofins HAS to give up market share. Ouch. Eurofins in 2025 is the FSS in 2011. After spending shed loads of money to acquire and stabilise Cellmark, now we’re going to strip them of market share by giving it to new market entrants? If police are the contracting bodies, they will be reluctant to do that, but if they are not the contracting bodies, well then it won’t be their decision where the work is undertaken. If I was Eurofins, having chosen, for some mad reason, to buy Cellmark from the ashes, I would not be best pleased to have the rug pulled from under me having stepped in, at considerable costs, to prevent Cellmark from collapsing.

The market is tiny. Even with more cash. Ultimately over time, what starts off as a diverse ecosystem may become a market with one or two suppliers as the small innovative SMEs are gobbled up by the bigger fish. We’ll be back where we started, again. It’s too small a pond for a diverse market to be sustained long term….unless the market model becomes so successful that other nations take notice and want to replicate it, opening opportunities for the UK suppliers to enter there. Is that likely?

We have had 15 years of demonstrating the benefits of a private market, our politicians LOVE talking about how we are leading the world with the fastest DNA turnround times, but no other nation appears to be willing to devastate their systems of provision of forensic science to achieve the same. It is far more likely that nation governments in the global marketplace will merely sit back and allow England and Wales to continue with its experiment and allow us to take all the risks. They will then cherry pick the good stuff that emerges from that and find a way to incorporate those into their public sector models, without the baggage of having to deal with a private market of companies and all the risks that are associated with that.

Don’t get me wrong I too share the belief that a market can work, but to some degree it will have to be ‘a fake’ market where the government is heavily involved within it. We have had a fake market for years so that should not be something new, it’s just the fake market we had didn’t work. A ‘fake market’ model that works is not a model that is easily transferrable to the EU or the US or any other jurisdiction where regulations may be hostile to government acting in that way. So if you’re an innovative SME seeking growth in the ‘fake market’, is there a viable option for you that is not merely selling up to the bigger fish? If all market roads lead back to where we are now in the end, is it really worth the hassle?

The APPG came to this conclusion:

2.96 Frustratingly, our research did not lead us to the ‘perfect’ model for forensic science to which we could simply point with confidence. While many countries have a mixture of public and private based forensic expertise, on the whole, forensic delivery remains a publicly funded part of most justice systems. England and Wales are still the only jurisdiction to have a fully commercial delivery model, albeit this epithet is increasingly misleading given the ‘public’ police provision.

The problem with the public sector vs private sector debate is that in terms of delivery does a nation state want a public service which is slow and cumbersome, but stable and independent, or a private service that is fast and nimble and independent but inherently unstable? If the answer is that England and Wales wants the best from both models, the question which the APPG ,or anyone else, has been unable to solve is how is that achievable1?

In relation to the AFSP becoming a trade association, it’s problematic territory, how can the AFSP avoid being labelled as a cartel if it acts in this way and would it mean that public sector laboratories (currently members of it) would have to leave it? If they have to exit, that only leaves three members (if you consider EFS and CFS as a single entity) and how are the current objectives of the AFSP served if the public sector departs? Realistically, with Eurofins so dominant, they have the leverage to set the terms regardless, they don’t need a trade association to get what they want.

It is a feature of inquiries that existing organisations are seized upon as likely vehicles for solutions, assigning them jobs to do, but sometimes they may not be the best or most appropriate choice.

Does the market need economic regulation? If recent disasters from attempted entries into the forensic toxicology marketplace and the cycle of doom of FSPs exiting the market are a guide arguably it does, but could stability in the market be achieved in other ways? Is the market size big enough to warrant economic regulation like an OFWAT or OFGEM etc? Neither of those regulatory models prevented the crises in the water or energy markets, soooo………

#10-11 “Regional provision but with boundaries”

The precarity of the forensic market and its monopolisation pose significant risks to the operation of the criminal justice system. If the forensic market cannot be pulled out of the graveyard spiral, it may become inevitable that forensic provision will be ‘re-nationalised’. There is little confidence that this could be effectively managed, and it would be both regressive and very costly. It might appear a better outcome than a pure monopoly, but what must be avoided is a national service under the control of the police. There must then be a pragmatic, short term strategy to ensure continuity with a medium-term regionalisation strategy to rationalise delivery and make it more efficient and effective. The police and forensic providers must collaborate to ensure that the ‘dual tracks’ of forensic science – the delivery of rapid results, coupled with more complex investigations, can be delivered.

Recommendation 10 – The Government must consult with all stakeholders involved in the criminal process – from crime scene to court and beyond - including prosecution, defence and appeal lawyers, judiciary, government departments, police and agencies such as the Legal Aid Agency and CCRC. Reform must seek to make forensic science work for all parties, meeting the requirements of good forensic science to ensure that crimes are properly investigated, trials are fair, and miscarriages of justice are prevented, uncovered and overturned.

Recommendation 11 - The Home Office and NPCC should rationalise current police service forensic facilities and arrangements reducing duplication, fragmentation and minimising national inconsistencies. Regional collaboration should be facilitated to ensure quality, consistency, and improved cost effectiveness, streamlining the boundary between policing and scientific support. Existing collaborations should continue to deliver current police services during the transition period to full regionalisation. This could include fingerprints, digital forensics, crime scene management, but not seek to expand into other areas.

That is a categorical “booo” to the concept of an FSS 2.0 under control of the police which the APPG believes is the outcome if the government do not intervene to save the market. As I am fundamentally opposed to national police control of forensic science, I share that view. Bravo APPG.

Regionalisation is obviously in keeping with the idea that we have too many police forces in England and Wales, and perhaps is in line with government’s long term plans for policing reform, but the key concept here is a halt to an expansion of activities of police forensic labs beyond the traditional ones in the short term.

#12 “National Forensic Science Institute”

In common with many countries around the world, and in line with many previous recommendations, the UK should be home to a National Forensic Science Institute (see also Chapter four).

Recommendation 12 - A National Forensic Science Institute (NFSI) should be created as the central authority on forensic science. The NFSI, working closely with police, lawyers, judiciary, providers, universities, industry, other government agencies, and the Regulator, should set strategic priorities, and coordinate and direct research and funding. The NFSI should set strategic priorities, and coordinate and direct research and funding. The NFSI should protect niche services, facilitating training and professional development.

The Forensic Science Service had only two things going for it politically (1) it advised the government independent from the police and (2) it was “the supplier of last resort”, which given its demise, has become an unfortunate moniker (historically speaking). Forensic scientists lost their voice when the FSS closed, the government has only listened to the police since. On that basis the idea of an institution having that voice restored is laudable.

If it is to be a national institute of course, it will need the Scots and the Northern Irish to be involved and that might be tricky (to put it mildly) in terms of its authority, with power devolved to the nations. In general though I’d be supportive of this, particularly if it took on the mantle of a ring fenced research and development budget for forensic science which could support universities in their work. In its final years the FSS had a £4 million budget for R&D, money which was diverted from forensic science elsewhere when the FSS was closed. I want that budget back where it belongs.

I do find its role as protecting niche services as a really interesting comment and I’ll come back to that later.

I don’t think this is a controversial recommendation and it should received broad, if not universal, support. From a marketing perspective, I would suggest it needs a better name though.

#13 “Police lose control over forensic science in the longer term”

The long-term aim should be to ensure that all forensic activities are delivered independently of the police. This vision for forensic science should take inspiration from Scotland, where all forensic activities, including scene investigation and fingerprinting, are no longer the preserve of the police. The NCoP, regional hubs, and the new National Forensic Science Institute should build close working relationships, but forensic science should be considered external to the police. Independence and impartiality are essential to both science and justice. Critically, the public perception of this independence is key to maintaining confidence and ensuring trust in policing. Forensic science must be led and driven by scientists, while lessons from the FSS should not be forgotten.

Recommendation 13 - A national forensic strategy must aim in the long term, to remove all forensic science provision from police oversight. Activities such as crime scene investigation, triaging, digital forensics, and fingerprints and other marks etc., should ultimately be undertaken by forensic scientists working independently of the police.

I’ve been barking on for years now that the Scots have got this right. The last 15 years have shown categorically what police control of forensic science delivers and it’s not fit for purpose.

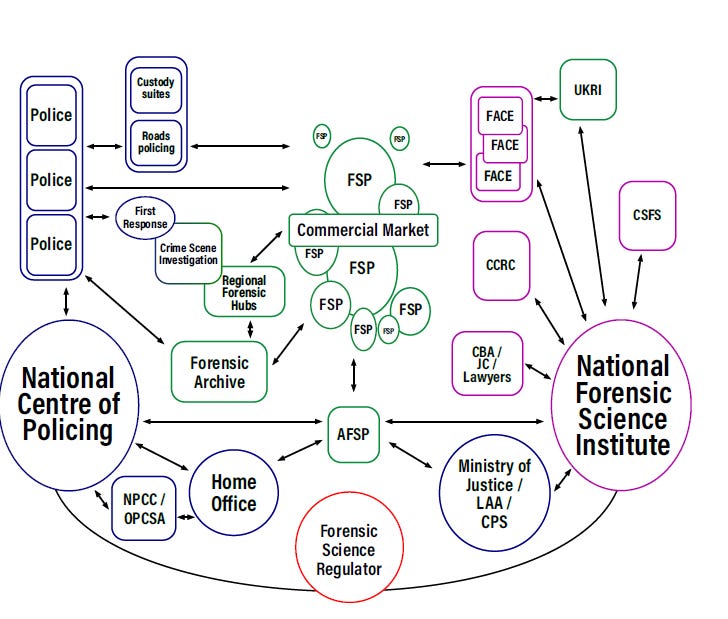

This is the service delivery model proposed by the APPG: I think as a first iteration, it’s not a bad place to start. The AFSP looks odd in it and I would consider “housing” the FSR in the National Forensic Science Institute. Some of the components in the model below are discussed in other sections of the report.

#17-19 “Experts for the defence”

Our adversarial system cannot work if defence experts become the preserve of the wealthy defendant or only used in high-cost serious trials. The lack of legal aid for defence experts means very few remain in the sector. Operational pressures on experts and defence solicitors in an area of very lo profit margins are driving more and more practitioners (scientific and legal) out of the sector. We have seen instances of this lack of domestic capacity and capability already impacting court management processes with trials delayed and disrupted. Even if they exist and can be located, experts may refuse instructions because of the paltry fees and unpredictability of trials.

Recommendation 17 - The Legal Aid Agency (LAA) should fund the commissioning of defence experts, at realistic rates and on prompt payment terms, to facilitate equality of arms. A review of government-imposed set rates for experts, and an upgrade of those fees in line with inflation is required. There should also be a presumption that expertise will be funded by the LAA.

Recommendation 18 - The Forensic Regulator should liaise with the Ministry of Justice, lawyers, LAA and others, to instigate processes to oversee the fair and accurate communication of forensic evidence.

Recommendation 19 - The National Forensic Science Institute (NFSI) should seek to ensure that there are experts nationally available to the defence. These experts must operate under the Forensic Science Regulator’s Codes of Practice which should be expanded to include case review and interpretation work with immediate effect.

A two-tier funding system in place for expertise that funds the prosecution at higher levels than the defence is by definition unfair. Of course it is right that defence experts are paid at acceptable rates, I’m not sure though that the LAA is the best we can do in making that happen. If the NFSI is to have responsibility for defence experts generally on a national level, then perhaps it should take responsibility for the funding of them too?

#22-23 “CCRC and Forensic Science”

It is critical for the avoidance of miscarriages of justice that forensic experts are engaged throughout the criminal process but once a miscarriage is suspected to have occurred ‘good’ science is essential. We rely upon experts to do this vital case review and investigative work and yet those working on miscarriages of justice have to fight to get their own testing done to challenge evidence.

Recommendation 22 - The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) should have within their permanent staff members who have scientific backgrounds. They should also have access to a panel of experts with broader knowledge and expertise via the NFSI. In all cases involving disputed forensic evidence a forensic expert should be involved in initial case screening, advising on a forensic strategy and overseeing scientific inquiries. A decision on whether to refer cases involving scientific evidence to the Court of Appeal should always involve staff with relevant scientific, not just policing, expertise.

Recommendation 23 - There must be a cultural change at the CCRC in favour of testing. Where the CCRC decides not to undertake forensic inquiries or further testing, their reasoning should be fully explained and made transparent. This should be open to scrutiny and challenge without recourse to legal action.

The CCRC is a wonderful idea and is an example of the UK doing something about miscarriages of justice that few other global jurisdictions have dared to do. BUT, after nearly 30 years, it finds itself in a dark place. Ideally, the goal of the CCRC should be not to exist at all, because if the CJS is doing its job perfectly, there should be no need for it. Until that day though, its role as the ultimate detector of quality failures within the criminal justice system is necessary, the question is what’s the most effective way for it to perform? Recent cases have shown that it is not testing enough. The recommendations above should go some way to mitigating against the situation where the CCRC had the means to detect a miscarriage of justice, failed to do so, only for that failure to be brutally exposed years later. Many of these cases have exposed just how difficult it is for scientists to predict the outcome of testing and the probative value of it as a means to determining whether the testing should be done. If there is more experience, and broader experience, available to the CCRC via the NFSI then I think on the whole this is a positive thing and should mitigate the conflicting risks of testing vs not testing, after all, the only guarantee is that if you don’t look for evidence you won’t find it.

#24-25 “Lost exhibits”

Obstacles to (re)testing of evidence clearly become insurmountable if that evidence is mishandled or lost. The retention and archiving of investigative materials need urgent national planning and investment, with post-conviction disclosure rules put in place.

Recommendation 24 - The Law Commission proposals on retention and archiving of evidence should be accepted, including the creation of a national storage capacity independent of the police (or expansion of the existing Forensic Archive). This should guarantee adherence to retention guidelines, with new Regulatory Codes of Practice to ensure the retention of all evidence with integrity.

Recommendation 25 - Representatives of appellants should be afforded disclosure of a detailed account of all archived investigative material and have access to materials for inspection/testing purposes upon request and having identified a suitable laboratory to conduct the work. Trial transcripts should be available to appellants at reasonable cost to assess how forensic evidence was presented during the trial.

This is a serious problem. Investigating cold cases and miscarriages of justice can become a lottery in terms of whether exhibits still exist, and if they do exist, whether they will be in a fit state to allow for new examinations. One issue that the APPG did not appear to consider in relation to this is the design of forensic packaging is generally not such that is suited to long term storage. Bulging brown paper bags held together with tape struggle to maintain structural integrity long term. I believe there is a lot that the packaging industry could do to mitigate that risk.

#26 “R not just D”

In finding a route to a strong and stable forensic science sector, the first step must be a renewed commitment to the scientific foundations of forensic science and the pre- eminent role of scientists. Forensic science can only be as good as the underpinning science. We must innovate in research and development so that the sector can confidently be relied upon for our criminal justice system, and once again become world leading. Research and development should also support basic research to fortify the underpinning science of forensic disciplines, with a strategy to prevent the further loss of specialisms.

Recommendation 26 - A national forensic science strategy, led by the NFSI and co- created with representation from all stakeholders, should drive reforms that will secure the survival and development of forensic science, conducted by independent scientists. Research should be undertaken to fortify the scientific underpinnings of forensic science, as well as operationally focussed research, horizon scanning and the development of methods and tools.

Ground truth’s important, no doubt.

#27 “Forensic Science serves the CJS not the police, R&D efforts should reflect that”

Forensic science should be recognised as part of our critical national infrastructure with a key role to play in the pursuit of the government’s missions. The sector urgently requires robust support that reinforces the fundamental principle that forensic science is the employment of scientific knowledge and skills for the benefit of society. This entails a re-configuration of which activities can be directed and delivered by police, while reserving all other roles for independent scientists. Efforts to further embed science and technology in policing are welcome, but these objectives must supplement efforts to reinforce forensic science, not supplant them. Any re-structuring of policing and police governance must facilitate the stability, and development of forensic science, so that forensic science can adapt in harmony with the maturation of this ‘science led’ policing. But forensic science must absolutely sustain and steer its discipline outwith the direct control of policing. The National Forensic Science Institute (NFSI) should supervise the production of a national strategy to secure national capacity and capabilities, in collaboration with stakeholders, but not embedded within police structures.

Recommendation 27 - The NFSI should oversee a national research strategy for forensic science include setting and renewing Areas of Research Interest (ARIs), agreed in collaboration with the National Centre for Policing (NCoP), the AFSP, and other stakeholders. This strategy should work in harmony with police ambitions to expand police science and technology capacity, not be subordinate to it.

This is forensic scientists reminding politicians where forensic science lies in the hierarchy, it is not a function of policing.

#28 “Forensic Science serves the CJS not the police, R&D efforts should reflect that”

The NFSI and UKRI should support a network of regional Forensic Centres of Excellence (F-ACEs), to create a vibrant forensic science ecosystem. Greater collaboration and partnerships with academia could reinforce both sectors, but there will need to be national cooperation and direction. The NFSI should conduct a full audit of forensic capacity and capabilities, building upon reviews conducted by the NPCC and FCN, including expertise and equipment available nationally, to take the first steps in protecting niche areas. The aim should be to consolidate the forensic sector and facilitate the ‘whole system’ approach with shared knowledge and inter- disciplinary expertise. National capacity could then be created or extended, to use forensic science more effectively for ‘intelligence’ (preventing and disrupting crime) as well as for evidence presented in the courtroom.

Recommendation 28 - The NFSI should support a network of Forensic Academic Centres of Excellence (F-ACEs) which bring together forensic academics, researchers, industry and police. This network should facilitate a ‘whole system’ approach to forensic science, where a shared understanding of capacity and capabilities stimulates innovation and improvement, whilst motivating the next generation of scientists and retaining and embedding the expertise that remains.

Other than expressing a desire to protect niche areas, which gets a thumbs up from me, I don’t really have a clue what this means.

#29 “Future proofing forensic scientists”

There must be strong support for the recruitment and retention of scientists, husbanding experience where it remains and ensuring the education and training of the next generation of forensic scientists is appropriate to both existing and new techniques and methodologies. Advances in forensic science and technology will be futile if there are no experts to utilise them and improve upon them. Our forensic scientists of today and tomorrow need encouragement and support to remain in the sector. Forensic scientists must be enabled to conduct research and develop their skills as well as their discipline. This must include holistic investigative strategies and interpretive skills, returning professional judgement to the centre of their professional role.

Recommendation 29 - The NFSI should assess staffing requirements and training needs for the future, with education and training designed with a view to growing a cadre of specialists while maintaining a body of more generalised forensic scientists who can work across multiple disciplines, thereby providing holistic approaches to complex investigations. A national strategy to preserve and reinvigorate specialisms within the NFSI and regional Forensic Academic Centres of Excellence, should include plans for the retention of highly skilled staff across a range of specialisms.

#30-32 “Save niche areas”

National capacity, and capabilities are rapidly diminishing and the benefits of diversity in forensic science are being squandered. Resourcing should be undertaken intelligently, taking evidence-based decisions and understanding where investment is most urgently needed to conserve diversity. This requires a clear assessment and articulation of the value of all forensic science disciplines. Saving and maintaining the full range of forensic disciplines and technologies should be prioritised. The unique and often vital links between all forensic techniques in investigating complex crimes demands that capabilities and techniques are maintained or difficult (often high profile) cases will remain unsolved, and opportunities to prevent and overturn miscarriages of justice will be lost.

Recommendation 30 - There must be an urgent survey of capacity and capabilities, including niche services, across England and Wales, and immediate plans initiated to retain what expertise remains. The NFSI strategy must ensure that through research and additional support, scientists remain at the forefront of developments. Disciplines and forensic techniques must be supported so they do not become outdated and reliant upon superseded methods.

Recommendation 31 - The Research Excellence Framework (REF) must establish a Unit of Assessment for forensic science meaning that further funding could be secured from government QR funding.

Recommendation 32 – The NFSI should work with NCoP to map unmet police needs and understand the reasons for the diminishing use of niche techniques. The essential maintenance and strengthening of national capacity and capabilities must be factored into an overall delivery model.

I’m all for protecting niche areas. In relation to forensic fibres as a niche area, having three (two) companies with three sets of expensive equipment that is idle most of the time, which is likely to be at the end of its financial lifespan, with a few aging but experienced and competent staff soon to retire and no way to justify training replacements owing to the lack of volume of cases, there is no way that niche areas can survive in the current system.

So where is the best home for fibres? Perhaps the NFSI should take some casework responsibility for niche areas if it really wants to protect them? Politicians prefer institutes that have money coming in after all. In the short term, the operating model of my previous laboratory, Contact Traces, could serve as a template for a niche activity housed within NFSI.

A system defined not just by public and private organisations, but also defined by activity, where niche areas retreat from the front line to safer ground could be the answer. The ground truth in forensic fibres emerged from the Home Office Central Research Establishment in Aldermaston in the 1970s, perhaps now is the time for fibres and other niche areas to return “home” so that they can not just be saved but grow and improve.

#34 “ISO21043 ?”

Forensic regulation needs to find a balance that allows for strict compliance as well as flexibility, especially for smaller providers and niche areas, without imposing prohibitive costs that reduces expert availability and stymies progress. There needs to be more assistance for those trying to achieve and maintain accreditation, ensuring that regulation supports high quality science, while sustaining the health and diversity of the whole forensic science eco-system. Forensic regulation should not be encouraging departures from the sector or limiting innovation, and consideration should continue to be given to the new ISO 21043 standard. A review should be carried out to determine if there is a more (cost) effective model for forensic quality assurance that avoids adverse outcomes. This review should cover the validity of the methodology for accrediting forensic science activities and the costs incurred by providers for UKAS accreditation.

Recommendation 34 - The impact of the forensic regulatory regime should be independently assessed with the Codes of Practice evaluated for their appropriateness for different practice areas and providers. There must be regulatory measures ensure that specialisms can be preserved while maintaining high quality science and compliance across all providers. Consideration should be given to the future adoption of the ISO 21043 standard and an assessment made of the UKAS accreditation process, to seek more cost-effective methods.

Final words of the APPG

During our work we were constantly reminded of past inquiries which stressed urgency, but whose recommendations were nevertheless largely ignored. These include the most recent House of Lords inquiry in 2019. If we continue to ignore our instruments and the alarms sounding, we should expect an overwhelmed and ineffectual criminal justice system producing more miscarriages of justice. If accepting the truth of the recent statement by Chi Onwurah MP: “We cannot have a society with no crime, the price would be too high. But we can aspire to have a society without injustice” then forensic science should be recognised as part of our critical national infrastructure. Forensic science remains one of the greatest protections we have against injustice and if we are serious about aspirations to a just society, the forensic science sector must be pulled out of its current graveyard spiral.

Not a criticism of the APPG, it’s a HUGE question.