How Fibres Transfer and Why it Matters

Fibres Deep Dive Pt 5. Sheddability, Physical contact, airborne stuff and fibres that hop from one surface to the next.

To Shed or not to Shed….

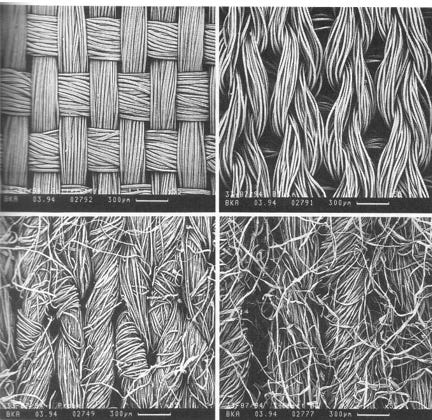

So this is how the surfaces of fabric appear using a scanning electron microscope, some are “smooth”, some are “hairy”, and some are “hairier” than others.

So not all surfaces are the same. In the case of the smooth surfaces, how on earth can any fibres transfer from them? The “hairier” a fabric becomes, the more fibres there are on the surface available for transfer. This is the concept that delivered perhaps the only word that forensic fibre experts have contributed to the English language- the term “sheddability” or “shedability”1 .

To give a better visual understanding of garments that show the spectrum of “sheddability” think of a waterproof jacket to a ridiculously mad hairy garment, and then everything in-between. In the textile world, as the modern environmentalists will tell you, by far the majority of garments shed their fibres, because relatively speaking, nobody is wearing the non-shedding stuff very often or for very long.

But smooth fabrics are not always what they seem either. What happens to them?

Well according to the wording of some Standard Operating Procedures I have seen in police forces, garments that do not shed their fibres are not worth pursuing in forensic fibre examinations. It seems like a fine idea in principle, but the question is how can you tell what sheds and what doesn’t? In terms of the images above, the waterproof jacket may seem like an obvious non-shedding garment just from looking at it, even perhaps through the narrow window of an evidence bag. But the thing is, what happens if you get an older, worn waterproof jacket? If it’s damaged with scrapes and cuts and cigarrette burns and what happens then?

For a really good discussion on the concept of sheddability and how best to assess it I recommend this paper2

An incredible case from the FSS, highlights these issues. The case of Antonio Imelia.

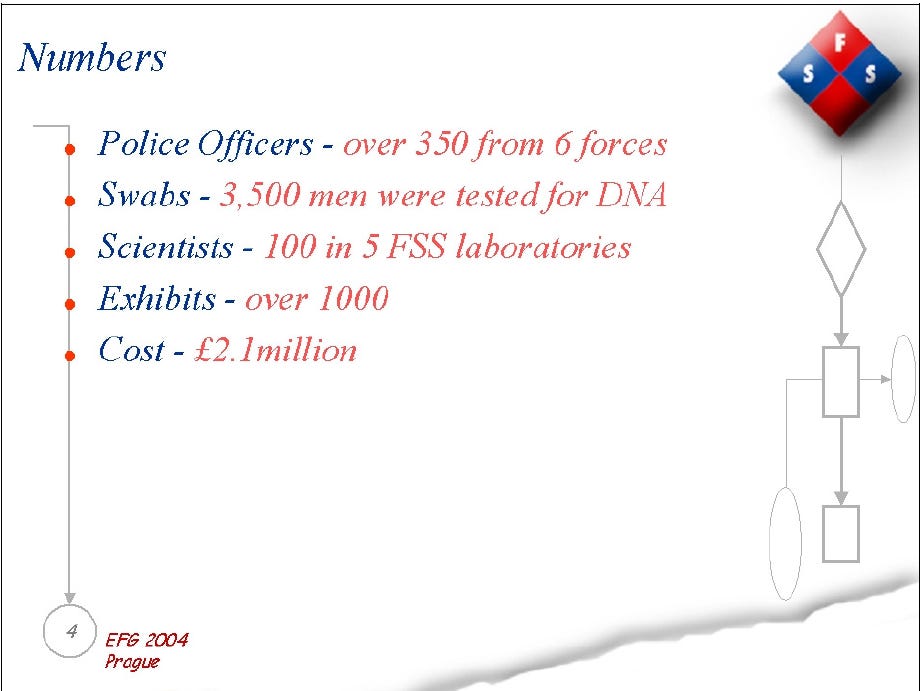

In 2001-2002 A series of serious rape, attempted rape, kidnap, and indecent assault offences involving 10 victims aged between 10 and 52 occurred around the M25.

Most victims didn’t see the clothing of their attacker clearly. It was generally believed that the offender disposed of the clothing he wore shortly after the attacks.

When Antonio Imelia was identified as a suspect (another story for another time) a lot of his clothing was seized by officers from his home address. The sheer scale of the work put into this case is outlined below, looking at it now, I sincerely do not believe that this level of resource exists in England and Wales today.

So how do scientists approach this from a textile fibre point of view? I refer you to my previous post on fibre persistence and the day in a life of our garments that we wear. We simply cannot escape our home environments, no matter what we do, there is always, always a trail to follow.

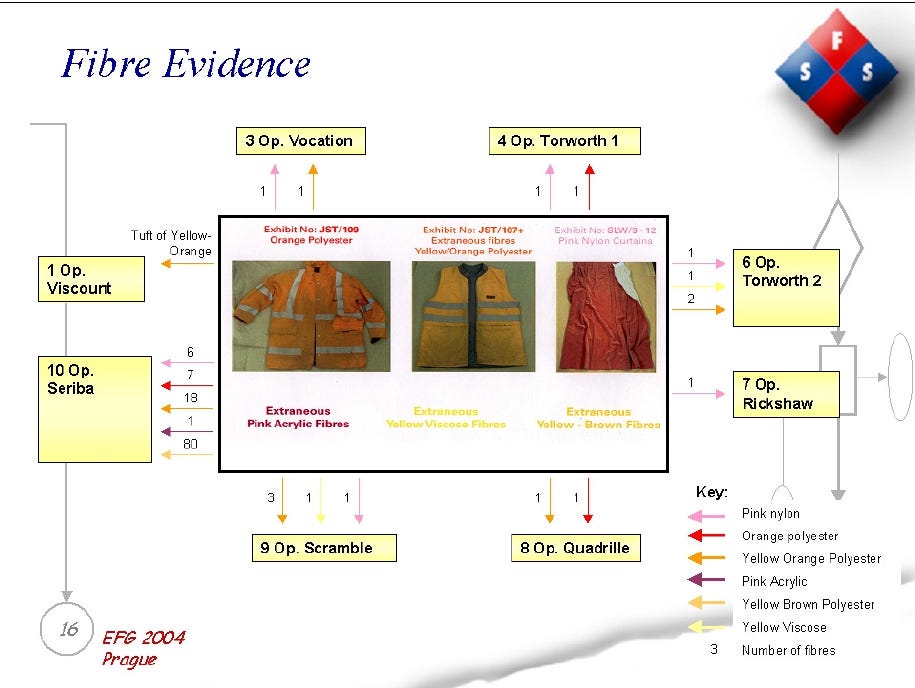

The FSS set about searching the garments seized from Imelia’s home environment to identify fibres that perhaps may have transferred to victims clothing when they were attacked. A brilliant piece of forensic work. But the point of this is not just an amazing forensic approach by the FSS, it is what they found on the victim’s clothing. Amongst several other fibre populations - they found fibres from clothing that would not typically be considered to be from garments that would shed their fibres. Orange fibres from Hi-Vis workwear supplied by Imelia’s employer3.

Searching for these fibre populations on the victims’ clothing produced outstanding results. Together with other evidence, a compelling picture was presentable by the prosecution seeking convictions for the offences. Of note of course, the number of offences where there was no DNA evidence found. Fast forward to today - would fibres have been done in any of these cases?

Bottom line, you can’t tell whether a garment is a suitable source of transferred fibres without testing it. You can’t test it, without opening the exhibit bag to find out. Assumptions kill cases.

Direct Transfer

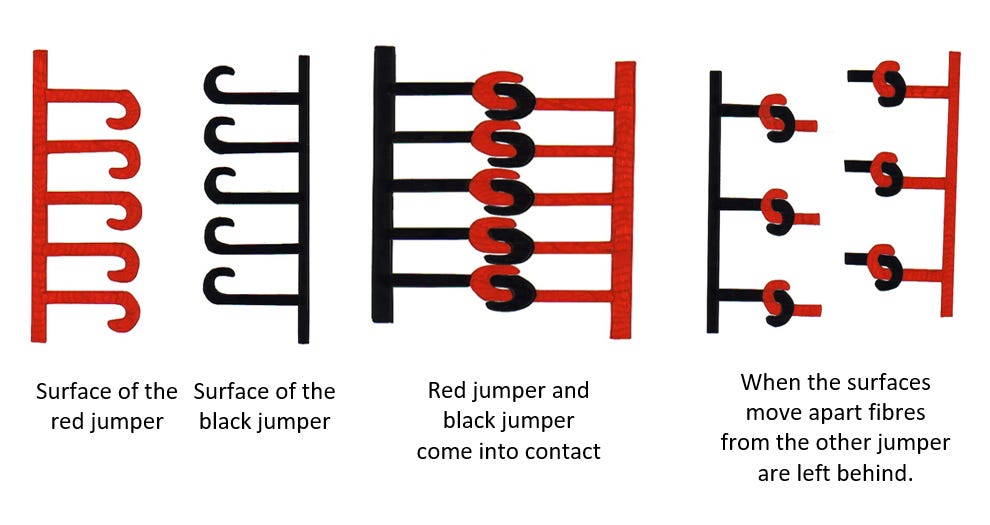

Classically, back in the day before Powerpoint and Microsoft paint and AI, I used to teach students and train forensic scientists in the basics of fibres by drawing out using coloured markers, a view of the surface of two garments that might make an engineer proud. Why? Because fibre transfer is all about the laws of physics (it all comes down to that in end) and engineers are very good at making physical concepts understandable in a way that human beings can visually grasp.

So, imagine two garments; one black, one red that come into contact with each other. Both garments shed their fibres and so have a dense population of their fibres on the surface at the point of contact. We can imagine that the fibres appear “hook-like”, via the friction the surfaces grab the loose fibres, transferring them from one surface to another and vice-versa.

Indirect Transfer

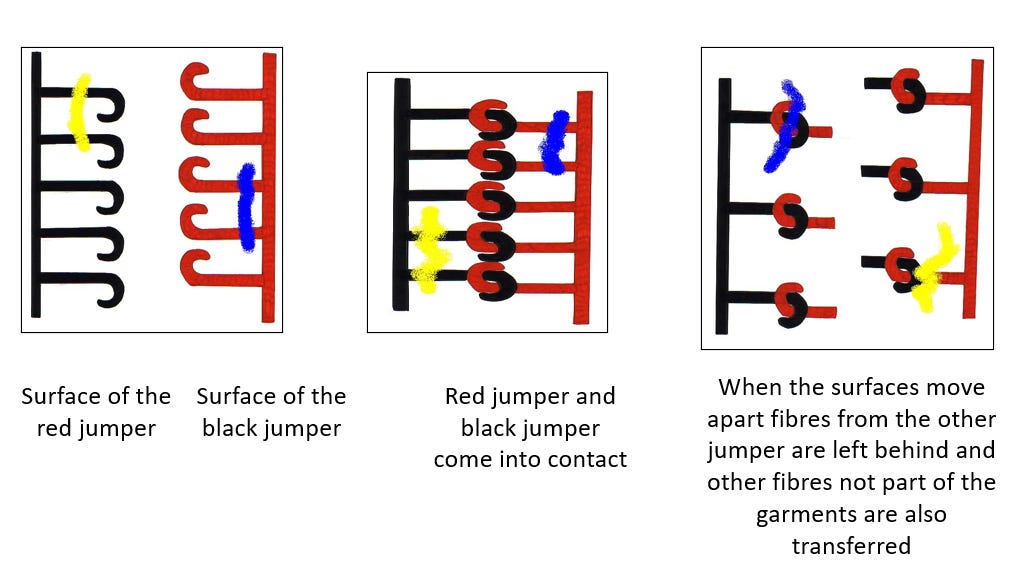

Ok, but we know from population studies that the surfaces of garments do not just contain fibres from those garments, there are thousands and thousands of other fibres present too, and they transfer too.

Here we have an illustration based on the previous example: a yellow fibre on the black garment and blue fibre on the red garment, transferring in the exchange during contact.

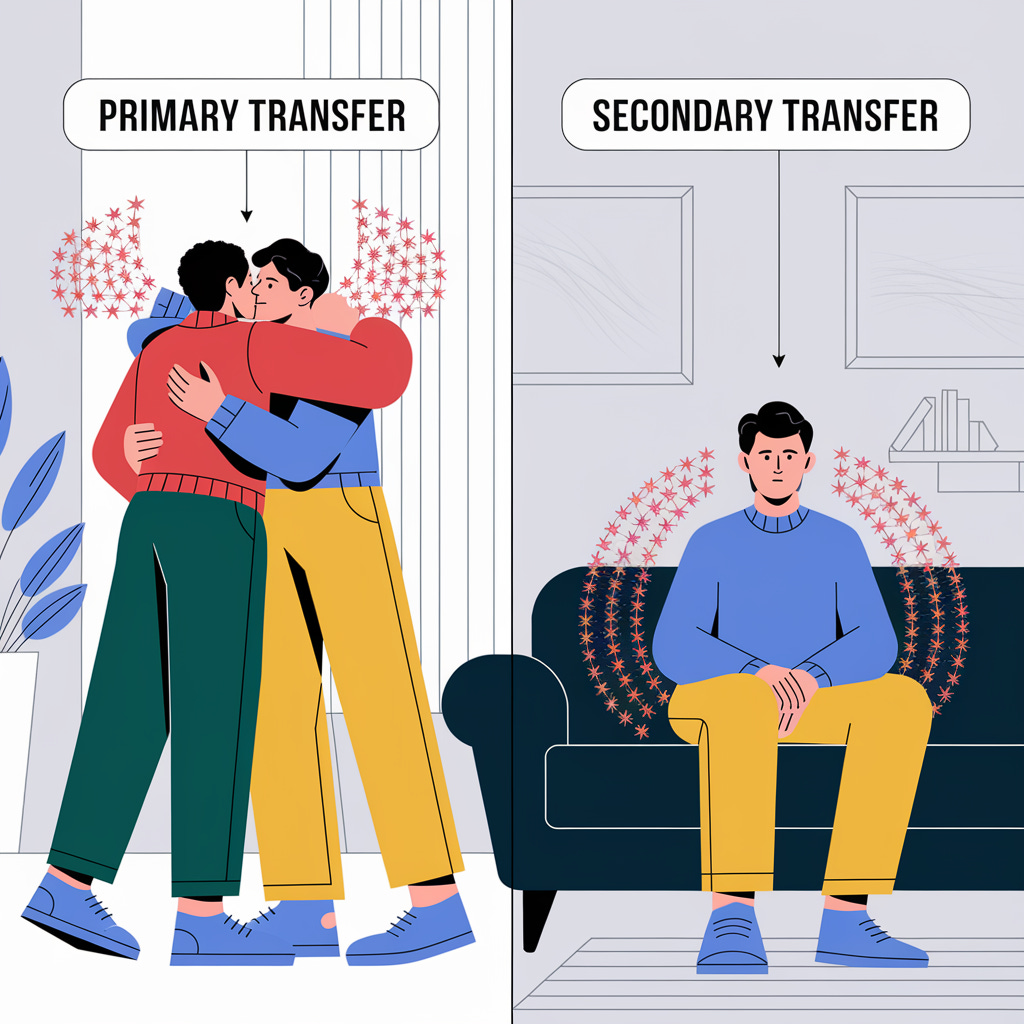

I’m not a great fan of the words “primary” and “secondary” when it comes to adjectives used to define transfer mechanisms, because in theory fibres could keep hopping from one surface to another ad inifinitum, and to label it in that way, the scientist would have to know the precise sequence of events - which is rare information for scientists to possess, but I’ll come back to that argument later when we talk about numbers of fibres transferring.

I prefer the terms, although not perfect, “direct” transfer for a primary transfer situation and “indirect” transfer for everything else. I do accept that “indirect” transfer is problemmatic language for the layperson, because it adds complexity to the mechanism that some would consider unnecessary, when really all it means is fibres that are not part of the construction of the garment which transfer during contact.

The world’s worst forensic soundbite “Every contact leaves a trace” is incomplete for fibre experts. It should read “Every contact leaves a trace which is the product of direct and indirect transfers which happen simultaneously”, but that is perhaps why forensic scientists don’t necessarily make good marketeers.

The most important take-away from this is that during every contact between two surfaces which shed their fibres, direct and indirect transfers are likely to happen every time, in every circumstance. Indirect transfers are not unusual.

Transfer and Contact

Every contact results in transfer of fibres, but not every fibre transferred comes from the source.

Ok in the classic thought experiment below, two people come into contact. Red fibres from one person’s top transfers to the other person’s blue top. The person wearing the blue top then sits on a sofa and transfers red fibres to the sofa, even though the person wearing the red top has never made physical contact with the sofa.

So fibres can be transferred without directly contacting the source garment, but it is still physical transfer of fibres from one surface to another.

What about airborne fibres?

Every human knows about dust, it is airborne, it contains a lot of heterogenous material, including skin cells, pollen. Textile fibres make up a proportion of airborne dust, which makes a lot of sense, because fibres are very tiny and very light and any disturbance to a textile’s surface will cause fibres to become airborne. They will then float around on air currents until they eventually settle on a surface somewhere.

So airborne fibres have always played a role in fibre transfer, but up until recently, it wasn’t really quantifiable.

A study on contactless airborne transfer of textile fibres between different garments in small compact semi-enclosed spaces

This excellent bit of work from Northumbria Uni constructed an experiment that optimised the potential for airborne fibres (in a very tight enclosed space) to settle on a garment in close proximity to it without making contact. To put the enclosed space into context, in the post covid world, the experiment placed donor and recipient garments inside the global standard for covid safe distancing, approx 2m away.

A really good piece of work, and as is always with research into the behaviour of single microscopic fibres in a macroscopic world, the complexities of the behaviour is laid bare.

For me, the key take-away is this sentence4:

In cases where a high number of transferred fibres have been found, the contribution of contactless transfer to that finding is likely to be negligible and thus would be of limited importance in any evidential interpretation. However, for those cases in which a small number of transferred fibres are recovered contactless transfer should be a greater consideration, particularly if case circumstances involve a passive interaction between a suspect and victim.

Unfortunately this doesn’t stop the press getting completely the wrong end of the stick:

The point of view that one matching found fibre can be ignored, is one to which the authors cannot subscribe. When only one matching fibre is found, it must be explained that it is impossible to prove that it is not an airborne contaminant.

If the Daily Mail5 was correct in its assertion that:

Study throws into question cases where a defendant's clothing fibres were found on a victim

It would call into question the body of knowledge that have been established over 50 years and this paper simply does not do that. It adds to our knowledge, it doesn’t subtract from it and it categorically does not, by itself, throw any previous cases into question.

So numbers of fibres on a surface matters, and no better place to start, in the next post, than at “time zero”, the point at which fibres are transferred onto a garment. We touched on this when we discussed persistence a few posts ago.

It’s such a new word that experts have yet to agree how best to spell it.

Shameless plug, for more on fibres from Hi-vis workwear see this study we did at Contact Traces some time ago. Merely because a fibre is distinctive, it does not necessarily mean it is of high evidential value.

Please do read the paper though, don’t just take my word for it.

Not a publication known for its nuance